1980, West Bengal: A director and his crew go to a village to shoot a film on the great Bengal Famine of 1943. During their stay in the village for a month at a dilapidated house that was formerly a zamindar’s palace, they discover that there is actually no need to go in ‘search’ of famine – it is an ever present realty in the villages of Bengal.

2006, New Delhi: A bunch of fun-loving, easy-going college kids wake up to a new responsibility of fighting against the corruption that plagues their nation, while shooting a documentary on the Terrorist Movement of the 1920s/early 30s in India. This they do to vindicate the life and ideals of a patriotic pilot friend who loses his life needlessly in a plane crash, but is falsely charged of flying irresponsibly after his death.

The first film, Akaler Sandhane (‘In Search of Famine’), is considered by many the best film of Mrinal Sen, one of the three gurus of Bengali cinema, who also pioneered the ‘New Wave’ cinema in India with his Bhuvan Shome (1967); the second film, Rang de Basanti (that takes its name from a patriotic song), by new-age Hindi film director Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, is a recent classic which would never have seen the light of day but for the faith shown in it by actor/producer Aamir Khan, a veritable game-changer of Bollywood.

Though 26 years apart, and in different languages, Akader Sandhane & Rang de Basanti have a lot in common – both are films within films; both examine the relationship between past and present; both start off as projects motivated principally by the idealistic director’s vision, but end up transforming the actors; and both take a landmark event of British India for investigation and end up showing that, in the case of India at least, “history repeats itself”!

Rang de Basanti: A grandfather’s diary; Technicolor & Sepia tone

In this film, it is actually a British girl, Sue McKinley, who indirectly inspires her cast. It is she who comes to India to direct the documentary and changes their bindaas attitude while filming the story of Bhagat Singh and his revolutionary friends. She is herself drawn to the story via the personal diary of her grandfather, James McKinley, who, as a Jailor in British India, had seen some of them from close quarters. The auditions that her contact in Delhi, Sonia, arranges for her, are a mess – but she eventually finds her characters in Sonia and her band of close friends.

Class-wise, they are a mixed group: son of a corrupt businessman, Karan (Siddharth) is filthy rich; while Daljeet or DJ (Aamir Khan) and Aslam (Kunal Kapoor) come from more moderate backgrounds. DJ’s mother (Kiron Kher) runs a dhaba, while Aslam’s family live in a Muslim ghetto: when he is dropped off from a car by his rich friends, the car stands ill at ease in the dingy neighbourhood. We don’t get to see Sukhi (Sharman Joshi) and Sonia’s (Soha Ali Khan) families, but they seem well-off. Ajay (Madhavan), Sonia’s boyfriend (the one whose death they all vindicate), comes from a military background; sacrificing for the nation runs in his blood. As his mother (Waheeda Rehman) tells Sue: “At one point, I had to accept that he (her husband) first belonged to the nation & then to me.” She, in fact, suffers a double loss – her husband to a war and her son to a highly avoidable accident. To this core group of Sonia is later added Laxman (Atul Agnhotri), a passionate political worker who firmly believes in the ideology of his right-wing, Hindu political party. It is he who undergoes the greatest transformation in the film, after the Machiavellian side of his political mentor is exposed.

The terrorist movement comes alive in Sue’s grandfather’s diary in a very interesting and different way – seen from the perspective of a sympathetic and impressionable man, torn between being a British jailor and a devout Christian, and willing to take blame for the wrongs that the British have done in India. Hence, about the famous Kakori Train Robbery by the revolutionaries in 1925 (the principal aim of which was to loot government money to buy arms), he says:

After Kakori, nothing was ever the same again. It was a resounding slap on the face of the British government. But we had only ourselves to blame for it, because what we heard was the echo of our own gun-shots. The Jallianwalabagh massacre had turned peace-loving Indians into angry men. This was the time when Bhagat Singh relinquished his pen & took up arms instead to write his destiny.

And while torturing Ram Prasad Bismil & Asfaqullah Khan in jail, he confesses:

Killing a man by slow degrees: I was told that with time, this task would become easy, but it didn’t happen so with me. We kept torturing them – but we could break neither Bismil nor Asfaq. It was as if they had made friendship with pain. They didn’t break; in fact, they did something that I had never seen before. When we were breaking their bodies, perhaps it was their poetry that kept their souls alive. When we failed [with physical torture], we adopted a different strategy….

Halfway through the film, there is an unusual twist, when the youngsters are suddenly forced to live out the story they enact in the documentary. The revolutionaries of the 1930s were fighting against an imperialist power and its unjust laws; the college kids in 2006 end up fighting the rank corruption of their contemporary government. 50 years after independence and 70 years after the revolutionary movement, the actual problem in India thus remains the same – the abuse of power by those who wield it. Only the actors have changed!

History is seamlessly interwoven with the narrative present in Rang de Basanti. The revolutionary chapter of India’s struggle for freedom is well-known, but even those who are not familiar with it (India’s Generation NEXT?) will have no problems understanding the film; as history does not sit heavy on it, it simply comes alive! And one of the ways in which the two time-frames are distinguished in the film is by the use of colour. The present is shot in Technicolor and the 1930s in Sepia tone (with only the Jallianwalabagh sequences in black and white). Throughout the film, there are many smooth and beautiful transitions from one to the next. But after Ajay’s death, the past and present coalesce: the group’s present becomes immanent with their characters’ past, to the point that they speak both as themselves and as the characters they enact.

Where Mehra scores: parallels, characterization & music

The sepia-tinted story of Bhagat Singh is something that every Indian (at least of my generation) knows by heart. Mehra does a very intelligent re-telling of its highlights, sans the controversial bits involving Gandhi i.e. – about Gandhi’s withdrawal of the Non-cooperation movement in 1922, post Chauri Chaura, as one of the main reasons for renewed terrorist activity in the 1920s & the debate as to whether or not he pleaded Bhagat’s Singh’s case enough before the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, in 1931. (This controversial part is bravely featured in Rajkumar Santoshi’s The Legend of Bhagat Singh – with Ajay Devgan in the lead role – the best among the spate of films to come out on the Punjabi martyr in 2002).

Mehra does not follow the beaten track; instead he creates two stories. And it is in the ingenious parallels that he draws between them – between the past and the present, between the contemporary lives of the college kids on the one hand with the challenges faced by the revolutionaries on the other – where he really scores. The constant surprise element in the plot that this inevitably results in also successfully sustains the viewer’s interest till the end.

The parallels:

| Past | Present |

| Jallianwalabagh Massacre, 1919 – where Gen. Dwyer’s men open fire on peaceful protestors without warning | Killing of pilot Ajay Rathod & passengers in a MiG plane – that was doomed to crash because of its faulty parts. (100 others already had over a decade, claiming the life of 30 IAF pilots). An instance of ‘high level corruption’ in which the Defence Minister, the head of a political party (Shastriji, Laxman’s mentor) & a businessman (Singhania, Karan’s father) were all complicit. |

| Demonstration against Simon Commission in Lahore, led by Lala Lajpat Rai, 1927. | Demonstration at India Gate, New Delhi, led by Ajay’s mother & his friends – to vindicate his reputation that was being sullied in the media. |

| Decision to kill SP Scott to avenge Lala’s death; ASP Saunders killed instead. | Decision to kill the Defence Minister to avenge Ajay’s death & his mother’s fatal condition. |

| Throwing of bomb in the Assembly “so that the deaf can hear” | Hijacking All India Radio (AIR) station & live radio chat with people across India |

| Hanged by the British Government, 1931 | Killed by paramilitary force |

Till today, Bhagat Singh remains the most famous and feted Indian revolutionary of his generation – partly because of his incredible popularity, which, at the time of his death at the tender age of 23, rivalled that of Gandhi’s. Hence, whenever there has been a biopic (the 1965 Manoj Kumar hit, Shaheed, being a case in point), the tendency has been to mainly focus on his life and heroism – while treating the others as more or less satellites. Even in Santoshi’s exhaustive and inclusive treatment of the revolutionary movement, that showed the synergy and solidarity between the Punjabi and Bengali rebels of the time, the spotlight never wavers from Bhagat Singh. Rakeysh Mehra avoids this pitfall. He chooses seven revolutionaries for his plot – Chandrasekhar Azad, Ram Prasad Bismil, Asfaqulla Khan, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Durga Bhabi & Banwarilal – and gives all of them adequate footage in the film. The friendship between Bismil and Asfaq, especially, is delineated lovingly and is of great importance in the film – as their bond rubs off on the actors who play their parts as well, culminating in Laxman’s apology to Aslam for his insulting and rude behaviour towards him all through, just because he was a Muslim. It struck a chord in post-Godhra India, with fraught Hindu-Muslim relations in many parts of the country in its wake.

The other great USP of the film is its music by A. R. Rahman. Rahman had been the composer in Santoshi’s film as well, but in Rang de Basanti, he excels himself. It is hard to choose from the 6 refreshingly new-sounding, widely different tracks, by widely different singers. MY favourite is not a song, but a poem – the famous ‘Sarfaroshi ki tamanna aaj hamare dil mein hain’ that has always been associated with the young revolutionaries and has become a part of their legend. What I like is both the picturization of the poem AND its rendition by Aamir Khan.

It is a poem of fearless patriotism – but also of blood and sacrifice, and ruthless determination. The beauty of a gifted singer’s voice (be it a Mohammad Rafi in the 60s or a Sonu Nigam in 2002) has always done justice to the romantic idealism in the lyrics; but no rendition on screen has ever captured the raw appeal of blood sacrifice that Aamir Khan manages to convey in his low sinister voice, even as the chorus join in a rising crescendo of collective oath-taking. I love the sinister quality of the whole track, so different from the melody we are used to.

Akaler Sandhane: A feeling of Déjà vu

Watching Akaler Sandhane is to be constantly visited by a feeling of déjà vu. The most obvious comparison that comes to mind is of course Satyajit Ray’s Ashani Sanket (‘Distant Thunder’). But there are whole scenes that are reminiscent of others from Sen’s own earlier films – Baishey Sravan (‘Wedding Anniversary’, 1960), Calcutta ’71 (1972) and Chorus (1974). What is common to all of them – whether they are set in rural Bengal or Calcutta – are poverty and hunger.

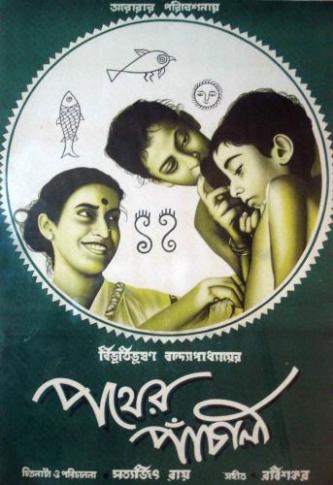

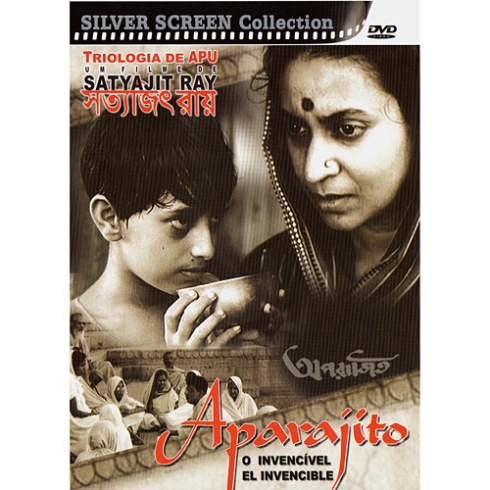

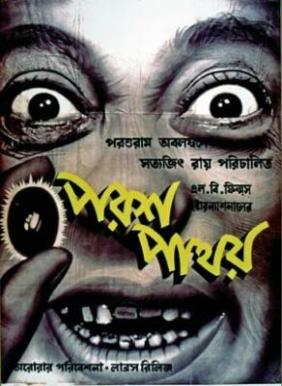

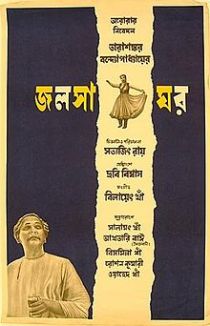

It is salutary to remember here that all the three greats of Bengali cinema – Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen – have dealt with poverty (as have other distinguished directors). The subject is unavoidable for any serious filmmaker in India. But they differed substantially in their treatment, in the stories they chose to show that poverty. Many of Ray’s films are set in rural Bengal, all of which happen to be adaptations of well-known Bengali novels or short stories. In Pather Panchali (‘Song of the Little Road’, 1955) – the first and most famous of them all – Ray, following the spirit of Bibhuti Bhushan’s novel, depicts a poor Brahmin family without forgetting to portray the dignity of their lives or the beauty of the countryside that surrounds them (seen as they are through the eyes of a child). In stark contrast stands Ghatak’s ‘Partition trilogy’, which unforgettably records the trauma and destitution of East Bengali refugees in the aftermath of India’s partition. Sen was preoccupied with this theme for a long period of time: an earlier phase of passionate indictments against poverty and exploitation (in the films mentioned above and his ‘Calcutta trilogy’) later gave way to more introspective studies of lower middle-class life and morality, where poverty is either a constant threat or intrudes indirectly (Ek Din Pratidin, 1979; Kharij, 1982). Akaler Sandhane, his 19th feature, belonged to this latter phase.

There is however one direct line of continuation between Sen’s ‘Calcutta trilogy’ and Akaler Sandhane – in the character of the director, who is never named in the film. Dhritiman Chatterjee, who plays the director here, had also played the lead in Padatik (‘The Foot Soldier’, 1973, the last part of the trilogy); and his socially conscious filmmaker can be easily seen as a new avatar of the Naxal revolutionary of a decade ago. He takes his art very seriously. Hence he is furious when one of his main leads plucks her brow even after being expressly told not to do so – as she was playing Malati, a destitute village woman who is forced to turn to prostitution because of dire poverty. Debika, the actress, used to the conventions of commercial cinema, where the female lead is always supposed to look beautiful, cannot imagine standing before the camera without at least the rudiments of makeup. “Saddha, sraddha…”, the director hollers at her, when she says this. “Respect, respect… you utterly lack respect for your character. Do you realize your enormous responsibility as an artist? As Malati, you will symbolize the countless wretched women who fell from grace and died during the famine.”

3 Scenes where 1943 & 1980 collapse

Unlike Rang de Basanti, Akaler Sandhane does not use colour to distinguish the two narrative time-frames – the famine of 1943 and a film-shooting about it in 1980. Instead, it effortlessly moves back and forth in time, continually collapsing 1980 and 1943 through the shooting sequences and the lived lives of the villagers. I would like to highlight three such moments in the film.

‘Spot-the-famine’ contest

A few days into their shooting, when sudden rains stall their work, the cast gather in a room of the huge decrepit palace to chill out; and over endless cups of tea and cigarettes and planning the dinner menu, they play ‘spot-the-famine’ contest. The director shows them a series of famine photographs culled from newspaper offices, archives and personal collections, and asks them to date the exhibits. Since the 1943 famine is the most well-known, quite a few err in thinking that all the photographs are from that period – but they are not. Almost identical ones are from 1959 (when there was a Food Riot in Calcutta) and 1971 (when Bangladeshi refugees flooded West Bengal during their War of Independence). Another tricky one is that of the Buddha – as a skeletal yogi sitting in the lotus position – which is actually a photograph of a statue belonging to the Gandhara period!

Sabitri & Durga: For a handful of rice…

In the ‘film-within-a-film’, Sabitri is the wife of a destitute farmer whose family of four (including the old father and the new-born) has been starving for weeks. But the men refuse to yield their last patch of land to the moneylender, who pursues them without success. Sabitri then resorts to the only choice left to her. She spends an evening with a contractor from Calcutta, and brings home rice and kerosene oil – essentials that have long vanished from the market. Malati (whom we don’t see), who has already turned to prostitution, helps her in this. (One is reminded of Sandhya Ray’s character in Asani Sanket – selling herself to an ogre for rice). Sabitri’s encounter with the contractor is not shown: that is irrelevant. What is not is the husband’s reaction when she is back home late at night. Without her uttering a single word, he knows in his bones the story behind that handful of rice and rages in impotent fury, even as a blank-faced Sabitri quietly goes about her task of putting the rice to boil and comforting her sick infant. Unable to elicit any response from her, her husband smashes all the utensils in the kitchen and is about to dash the baby to the ground when Sabitri screams and stops him. Her scream in the shoot coincides with Durga’s in the crowded audience. For the scene Durga saw enacted before her eyes was a slice of her own life; and she would herself re-live the scene only days later.

Her story, though she lives four decades after the 1943 famine, is the same as Sabitri’s: her husband lost an arm in an accident in his factory and has been at home ever since. What she earns as a part-time maid in several houses is not enough for the sustenance of the family. The coming of the film crew has however temporarily increased her income and she has even been persuaded by the director’s right-hand man to play the part of Malati in the film. (Debika, the actress supposed to do the role, left in the middle in a huff out of vanity, and the director was having a tough time trying to find a replacement for her). Though initially extremely shy, Durga decides to take the challenge, and confronts her husband in a situation identical to that of Sabitri’s. But she ultimately doesn’t act, leaving the director in the lurch.

Sabitri & Durga: No end in sight…

The film within the film ends with Sabitri leaving the village alone – after the death of her infant and husband – part of a long line of emaciated beings going to the city in search of food. While the others proceed, she pauses after a while and breaks down in unspeakable sorrow. Sen’s film ends with a still of Durga, rapidly receding in the background, with a voiceover ending her tale in three lines: “Durga is alone. Her infant died. Her husband cannot be found.”

Though Durga herself does not say anything, a poem could stand in for her – the poem that Sen had used as a chorus for the stories in Calcutta ’71; and which begins and ends the tale of a Naxal rebel killed in a police encounter:

I am twenty,

In my twenty years, I’ve been walking for a thousand;

For a thousand years, I’ve been walking – pushing through poverty, destitution and death,

For a thousand years, I’ve been a witness to history – the history of poverty, of deprivation, of exploitation,

For a thousand years… [My translation]

Akaler Sandhane is an incredibly complex film that works at several levels: it is not just about the relation between the past and the present, but also about art and reality and the limits of representation. It also dramatizes another great divide in India – that between the village and the city. While the past and present may come together in surprizing and shocking ways, the gulf between the city and the village remains. For the film crew in Akaler Sandhane, this gulf with the villagers only widens after an initial curious encounter. Their alien and seemingly exploitative presence is at first tolerated and then increasingly resisted as an intrusion by the villagers. Consequently, the film unit has to pack up and leave for Calcutta, forced to shoot the rest of the film in the studios. What haunts the viewer, however, is not the fate of the conscientious director’s film, but the fate of Durga in the village.

Both Rang de Basanti & Akaler Sandhane tell stories of people who were at the receiving end of the “white man’s burden” in India – about fearless, selfless, patriotic young men who went smiling to the gallows in the name of freedom; and millions of ordinary, innocent people who needlessly died of hunger, not knowing they were pawns in a gigantic machinery of exploitation. Though both films are partly set in British India, they are not about the British rule. Neither are they about contemporary politics. They are ultimately about moral principles – justice and equality – that always have to be fought for!

![1297103623_Jatugriha[1]](https://rituparnasandilya.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/1297103623_jatugriha11.jpg?w=225&h=300)